- Wild animals

- >>

- Fish

The gudgeon is distributed throughout almost all of Europe and the Asian part of Russia: these small fish can be found in large quantities in almost any river. They live near the bottom and feed on various small animals. They are found in schools, so you can catch a lot at once in a short time, but fishermen prefer other prey, and they are more often used as bait.

Origin of the species and description

Photo: Peskar

Fish are very ancient creatures, they appeared over 520 million years ago. The first of them looked more like worms than fish, but then, 420 million years ago, the ray-finned class arose - the principle of the structure of their fins was the same as that of modern fish.

This is not surprising, since the vast majority of fish inhabiting the planet today, including minnows, belong specifically to the ray-finned species. But over the past hundreds of millions of years, they have traveled a long evolutionary path; first, those species that inhabited our planet in the Paleozoic era, and then the representatives of the Mesozoic fauna that replaced them, became extinct.

Video: Minnow

Most modern species, with the exception of rare “living fossils,” arose already in the Cenozoic era, and this fully applies to fish. It was they who began to dominate the water at this time, and primarily the clade of bony fish - dominance passed to them from sharks.

Only then did the first cyprinids appear - and it is to this family that minnows belong. This happened about 30 million years ago. It is not known for certain when the gudgeons themselves arose; there are finds dating back 1 million years, but it is possible that this happened noticeably earlier.

The genus was described as J-L. de Cuvier in 1816, received the name Gobio. It includes many species and new ones continue to be described. For example, only in 2015 a scientific description of the species tchangi was made, and a year later artvinicus.

Habitats

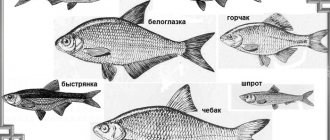

In Russia, gudgeons live in the rivers of the Volga and Caspian Sea basins, as well as in the Far East and Primorsky Territory. This fish is an object of sport and recreational fishing and serves as food for valuable breeds of predatory fish. The gudgeon belongs to the carp family and includes 14 species , the most studied of which are the following:

- Ordinary. Inhabits the rivers of Europe, with the exception of the Danube and Dniester basins. And it is also not found on the Apennine and Iberian Peninsulas.

- North Caucasian long-whiskered. This species is found in the upper reaches of the Kuma River and the basin of the Terek and Sulak rivers. It also lives in the rivers of northern Azerbaijan.

- Kuban long-whiskered. A small non-commercial species, reaching a length of 12 cm. It is endemic to the Kuban River and its left tributary, the Laba River.

- Kessler's minnow. Distributed in the rivers of the Black Sea basin (Dniester, Danube) and in the Vistula River, which flows into the Baltic Sea. Grows up to 13 cm.

- Amur whitefin. It lives in the middle and lower reaches of the Amur River. Reaches a length of 11.5 cm.

- Khankinsky. In the Amur basin, this species lives everywhere, but the largest number of it is found in the lower reaches of the river and in Lake Khanka. This species is also known in Mongolia, China and Japan.

- Manchurian. It lives in the rivers of the Amur basin, as well as on the Korean Peninsula and in the Liaohe River.

There are a number of habitats that have been studied

Appearance and features

Photo: What a minnow looks like

The length of an adult gudgeon reaches 10-15 cm, but can grow to larger sizes - 20-22 cm. Its body near the abdomen is slightly flattened. A very characteristic feature is antennae, one on each side. The mouth of this fish is located at the bottom - this makes it more convenient for it to eat living creatures or plants, swimming above the very bottom.

There are two rows of teeth in the mouth, their tips are slightly curved. The head is flattened, the snout of the fish is long, its upper jaw protrudes above the lower jaw. The upper part of the body is brown with a greenish tint, the sides are silvery. The fish is covered with dark spots, sometimes so many of them that they merge into stripes.

This coloring allows it to remain unnoticeable when it swims near the bottom: from above, the fish may appear to be part of the mud or a lump of algae. In the water, the gudgeon can be distinguished by its pectoral fins: they are large relative to the body and widely spaced, as a result of which, when it swims, it looks almost triangular.

Its dorsal and anal fins are short, without serrated rays. The fins are light gray, with a slight brown tint, except for the tail and dorsal - they are brown, but as if faded. As they grow older, minnows gradually darken more and more.

Interesting fact: Minnows can communicate with each other using squeaks and squeaks - this is a rather rare skill for fish, although not unique.

How to choose a place and what to catch minnows with

Cool flowing water bodies with a hard bottom (sand, stone, pebbles, clay) can be considered promising for fishing. Sandy shallow waters, rocky river riffles, well-heated pits and dumps at moderate depths are optimal for gudgeon fishing.

The gudgeon will only bite on bait of animal origin. As for bread, dough, cereals and other vegetable attachments, they are of little use.

The iron ore worm can be considered a universal bait, but since it is included in the Red Book of the Russian Federation, it is better to abandon this idea and use other baits.

The gudgeon is well caught on bloodworms, maggots, honeydew and caddis larvae, and dung worms. The first two are planted either individually or in a bunch of several pieces. It is best to use the worm in sections, without forming a tail that hangs down too long.

Fishing for gudgeon does not require bait. The exception is earthen balls with the addition of chopped worms and bloodworms, which, when released into the water, create a cloud of turbidity that attracts fish.

To learn more:

Tench: description of fish, habitats, spawning and fishing methods

Where does the gudgeon live?

Photo: Minnow in the river

Distributed in the northern part of Europe: it can be found in almost every river flowing into the seas of the Arctic Ocean. What all these rivers have in common is that their waters are relatively cold—that’s exactly what minnows like. That is why they are found less frequently in the warm rivers of southern Europe that carry water to the Mediterranean Sea - they are more favorable for other fish.

However, they also live in some of the rivers of the Mediterranean basin, for example, in the Rhone. They also inhabit the rivers of the Black Sea basin: Danube, Dnieper, Dniester. They live in most of the Russian rivers west of the Ural Mountains, such as the Volga, Don and Ural.

They live in the waters of Scandinavia. They were introduced into Scotland, Ireland and Italy, multiplied and have now become common inhabitants of water bodies there. In the Asian part of Russia they are found all the way to Primorye, and are also found in the reservoirs of Central Asia.

Apart from water temperature, the principles by which gudgeons disperse have not been reliably established: these fish can be found in large calm rivers and stormy mountain rivers, and even in streams; they are found in large lakes and very small ponds. It is only known that the cleaner and more oxygenated the water, the higher the likelihood of encountering them.

They also love ponds with a bottom made of crushed stone or sand. They live near the bottom in shallow water, and most often remain in the same place where they were born, if it is convenient enough and capable of feeding. Even if they have to migrate (usually the whole flock does this at once), they usually do not move long distances, but only a kilometer or a few.

Every autumn they go to deeper places, looking for where there is more silt, so that it will be warmer when the river is covered with ice. When a body of water begins to freeze, you can often see groups of minnows gathering near the springs, from which water continues to flow. Until the last minute, they try to find unfrozen areas with oxygen-saturated water.

In winter, they try to find a place where the water is warmer: they go into lakes or ponds, they can swim into underground waters or look for hot springs. More often they simply lie down in holes at the bottom and burrow under the silt. If gudgeons are placed in a lake with clean water, then they breed in it in a matter of years, but at the same time they do not reach the size of river ones.

Habits and nutrition

This predator prefers living organisms to vegetation, and is sometimes caught on artificial bait. Thanks to the sensitivity of its whiskers, it unerringly finds food among stones and sand. Its diet includes bottom invertebrates, mollusks, worms, mosquito larvae, insects, cyclops, and daphnia. In spring it feasts on the caviar of various fish. May also taste animal excrement.

In bodies of water where there is a current, it hunts from a so-called ambush. It hides in a small depression at the bottom and waits for the current to bring some insect, egg or small crustacean. Seeing prey, it sharply pushes off with its pectoral fins, grabs potential food and again hides in its shelter.

It hunts during the day, but at night it remains practically motionless. To prevent being carried away by the current, its fins rest against the bottom, which is why it is called a column or a table.

Recommended reading: How weather affects fishing

What does a gudgeon eat?

Photo: Common gudgeon

The gudgeon's diet includes:

- mayflies;

- insects;

- worms;

- shellfish;

- caviar;

- fry.

As you can see, this fish is a predator and prefers to feed on various small animals. Gudgeons can also eat plant food, but in rather small quantities, and they mainly obtain food for themselves by hunting, which they can conduct from morning to evening. They mostly spend this time examining the bottom, diligently looking for prey, sometimes they start digging, feeling everything with the help of sensitive antennae, from which nothing can hide.

Sometimes minnows can even set up an ambush in a place where the current is quite fast and carries a lot of prey. They hide next to the current, near some stone, wait until a small fish or some kind of mollusk swims by, and after waiting, they deftly snatch it.

In spring and early summer, when other fish go to spawn, minnows switch to feeding on eggs and fry, purposefully search for them and often swim in these searches from the bottom, sometimes to the very surface. Minnows are attracted to movement, and therefore, in order to lure them, they usually stir up the water.

Interesting fact: Although people rarely use gudgeons themselves as food, they are useful: their meat contains a lot of vitamins and microelements, and frequent consumption has a good effect on the condition of the cardiovascular system, bones and skin. They also contain a lot of iodine, which helps with thyroid problems. At the same time, the fat content of gudgeon meat is minimal, so it can be consumed during a diet or when recovering from an illness.

Biological features

The most common among all varieties is the common gudgeon. This is the largest of the genus. Its body length can reach 22 cm, but such individuals are rare. The bulk of representatives of this species grow up to 12-15 cm. The common gudgeon has the following structure:

- Head. Elongated in shape with a lower mouth, in the corners of which antennae are located, their length can be 5-8% of the length of the animal’s body.

- Eyes. Yellow in color, quite large compared to the size of the body.

- Body. It has a spindle-shaped shape, slightly flattened on the sides. Covered with large, silvery scales. From above, the body of the gudgeon is greenish-brown in color, and on the sides there are inclusions of small, dark blue or black spots.

- Fins. The caudal fin is practically not separated from the body and is covered with numerous black dots, which are also present on the dorsal fin. The pectoral fins are wide and have no dark markings.

These fish live in small schools, feed on the larvae of mosquitoes and mayflies, and adults eat the eggs of other fish. The common gudgeon is an excellent live bait when fishing for perch or pike.

The fish's eyes are yellow

Features of character and lifestyle

Photo: Minnow fish

Minnows are usually active during daylight hours; they are constantly looking for prey, mainly at the bottom, but in shallow water. The best chance of catching them is close to a rocky or sandy shore. At night, minnows rest, clinging to the bottom with their fins so that the current cannot carry them away during inactivity.

Usually, even before sunset, they hide among the plants near the rifts, so it’s convenient to catch them at this time if you know such places. But this does not always happen: if predators have settled near the minnows, hunting them and also active during the day, they try to hide and go out in search of food later, at dusk.

They see poorly in the dark, so in such cases they don’t have much time left, and the second period of activity occurs in the dawn hours. Such a change in the daily routine really helps to confuse predators, but it is only useful when there are no or few predatory fish in the reservoir that are active at dusk.

Minnows can swim quite quickly, including against a strong current, but usually do not show the energy expected from such a small fish: they like to rest and usually swim lazily, so they can be caught with a net.

Interesting fact: During the hottest days of summer, minnows become lethargic and vulnerable. At the peak of the heat just after noon, they rest for a long time near some stone, remaining motionless, for which they were nicknamed columnars.

Tackle for minnow

The best option for catching small fish is a float rod 4-6 meters long with light equipment:

- fishing line 0.1-0.2 mm;

- short leash 0.08-0.18 mm;

- hook No. 16-17;

- float 2-4 g;

- sinker 1.5-3 g.

For fishing, the “wiring” method is most often used. The immersion depth of the equipment must be set so that the sinker is at the bottom, and the float slowly drifts or is carried away by the current. Since the gudgeon bite is greedy and the fish immediately grabs the bait, hooking must be done when stopping or pulling the float under water.

In strong currents, it is convenient to fish with a “lying” float, setting the depth on the fishing rod more than necessary. Hooking the gudgeon should be done at the moment when the float begins to float. This serves as a signal that the fish has swallowed the bait and lifted the sinker off the bottom. The best fishing times are early morning and late evening. During the day, the gudgeon bites sluggishly and does not feed at all at night.

Social structure and reproduction

Photo: Peskar in Russia

On average, by the age of 3, minnows are ready to breed. At the same time, as at an earlier age, they continue to remain in the group. In such schools of minnows, fish of all ages coexist; joining together increases their chances of survival when attacked by a predator.

This makes it more likely that one of them will notice the attack earlier, and the predators will not be able to attack everyone at once, even if there are several of them, which means that most of the flock will be able to escape. But what the minnows don’t know is that some large predators are attracted precisely by their schooling lifestyle: it makes little sense for a large fish to hunt for one minnow, otherwise you can catch several at a time.

They spawn once a year, spawning begins after the water warms to 7-8 °C. In warmer latitudes this can happen in April, and in the north only in June. Spawning does not take place at once, but in portions and can last up to two months. One female can lay from 8 to 13 thousand eggs. She does this near the place where she lives, also in shallow water. Due to the fact that minnows splash noisily while laying eggs, they attract the attention of predators who begin to devour both the eggs and the minnows themselves, which is why this is the most dangerous time of the year for them.

The eggs are small and bluish. They have an adhesive shell, and therefore quickly stick to snags, stones or plants at the bottom, they are covered with sand or silt, after which it becomes difficult for other fish to find them to eat. Therefore, the most dangerous time for them is immediately after postponement. Immediately after emergence, the larvae have disproportionately large pectoral fins and prominent eyes. For 3-4 days they just lie on the bottom, they have no reaction to light at this time. After this period ends, they begin to actively feed on detritus and benthos: various small invertebrates living near the bottom.

At first they grow very quickly and, if there is enough food around, they reach a length of 6 cm in just three months. Then growth slows down and the gudgeon grows to a size of 12-14 cm by 3-4 years, then it is already considered fully grown and, although continues to grow, but very slowly. Life expectancy can reach 8-10 years, but since there are too many people willing to profit from minnows, few of them live to old age, most of them die at no more than 4-6 years. Minnows caught in the wild can live in an aquarium, but their life expectancy in such conditions is reduced - even young fish are unlikely to live more than 3 years.

Fish "Common gudgeon" photo and description

Latin name:

Gobio Gobio

Other names:

European gudgeon, Common Gudgeon (English)

Family:

Cyprinidae

Genus:

Minnows

Type:

freshwater

Lifestyle:

benthic

Diet type:

peaceful

Habitat:

Black Sea basin, Baltic Sea basin, Pacific Ocean basin, Mediterranean Sea basin, Caspian Sea basin

Appearance:

A small fish with an elongated, ridged body covered with large scales. The mouth is lower, arched, with one antennae at the corners. The lower lip is widely interrupted. The snout is long, twice the diameter of the eye. The eyes are relatively large.

The coloring is typical bottom, providing good camouflage on dark ground. The back is gray-brown, the sides are light, yellowish in large individuals. On the sides of the body there are about 10 large dark spots along the lateral line. The dorsal and caudal fins are gray-yellow, with rows of small dark spots, the remaining fins are colorless. The caudal fin is noticeably cut out. Reaches an age of 8-10 years, but rarely exceeds 3 years, a maximum length of 20 cm and a weight of 226 g, but the usual dimensions are no more than 12-15 cm. Females are larger than males.

Habitat and behavioral characteristics:

It lives in lakes, in the lower reaches of slow-flowing rivers, and in the upper reaches of fast-flowing rivers. It is found even in slightly saline waters of the Northern Baltic. Stays near the bottom. In summer it forms small accumulations in shallow water, in winter it moves to depth.

Widespread Eurasian species with a dispersed range. It is found from Portugal to the Amur basin and the rivers of the northwestern coast of the Sea of Japan. In Russia, it is common in water bodies of both the European (with the exception of the Kola Peninsula and North Karelia) and Asian parts. Not recorded east of the Yenisei, its range is interrupted here. The gudgeon reappears in the Amur basin and in the Tugur, Uda, Suifun and Tumannaya rivers; absent in the rivers of the Pacific slope located north of the Amur and Uda, in Kamchatka and Sakhalin. In Mongolia it is found in the Onon, Kerulen, Khalkhin Gol rivers and in lake. Buir-Nur. Found in China (the Yalu and Liaohe rivers), it reaches the Korean Peninsula. It is no longer available in Japan.

Nutrition Features:

It feeds on the larvae of chironomids, mayflies, caddis flies and other insects, as well as crustaceans and mollusks (peas), and in the spring it readily eats the eggs of other fish.

Reproduction:

It becomes sexually mature when it reaches a length of 8 cm. It breeds at night in spring and early summer (April-June), when the water warms up to 15° C. Spawning is portioned, along the current, in shallow places with a rocky-sandy bottom. Eggs with a diameter of 1.3-1.5 mm are glued to the ground. Fertility 1-3 thousand eggs. The eggs take about 8 days to develop. Larvae and fry eat plankton and other small invertebrates. The juveniles stay close to the shore, and as they grow, they move to deeper places.

GENDOW – Gobio fluviatilis L. In most of Russia – gudgeon; in some places along the Volga, as well as in the Perm province. - sand-tooth, sand-tooth; on the Don - sand tooth; on the Kama – sandstone; to Vologodsk. lips – sand; in the Urals - piskan; in Pskov - pesuk, piskushek; in Arkhangelsk - pestush; in Novaya Ladoga - scab, scab; to Novgorod. lips - mulyatka; on the Volkhov rapids - baraus; in Narva - krympa (Izhorian name); at the southern tip of Lake Onega - gulen; in the river Onega, according to Petrov, is a catfish. To Penzensk. lips (Dahl) – a slasher; according to Dahl, in some places - tugunok. To Voronezh. lips and in some in the localities of Little Russia it is incorrect - beaver; in general in southern Russia - column, column; in Kremenchug - pechkur, in Volynskaya and Podolsk. lips - cobble, cobbly, male. In Poland - kilb, kolb, ruzik; in the northwest lips - kurmel. The Estonians have yuri-lest, kivvi-kala, kor-yuri, grun-dilt; among the Izhorians - krimpe; in Latvian – pops, grundulis; head – Ulyan; vog. – otra; cherry – Shumuran, Oshma-kol; Chuvash – irash-pyutra, kutan; tat. - tash bash. See also below the names given to distinguish both types of gudgeon.

The appearance of this small fish is more or less known to everyone: it is easily recognized by its large scales, cylindrical body and two small antennae that lie at the corners of its mouth. In quite rare cases, the gudgeon reaches four to four and a half inches in length and thickness of the thumb, as, for example, in the middle Volga; for the most part it is no more than three. Its blocky body, devoid of mucus, is greenish-brown on top and covered with bluish or blackish spots, which sometimes merge on the sides and form a dark stripe; abdomen yellowish, silvery; the dorsal and caudal fins are speckled with dark brown spots, which are usually located in several regular rows; all fins are grayish; yellow eyes. The gudgeon's pharyngeal teeth (7-8 on each side) are arranged in two rows, and their rim is curved at the top with a hook.

But in general, the gudgeon presents great deviations both in color (old ones are always darker) and in the shape of the body and head. It has been noticed that in the northern parts of Russia the gudgeon is much sharper than in the south; in Moscow province. all fishermen distinguish from the ordinary black minnow (in Kolomna - oxbow lake) - the accelerated blue minnow, or sandstone, which is smaller in stature, rarely more than 2 inches or 4 inches, oblong, with a continuous blue stripe on the sides and highly translucent insides; the caudal and dorsal fins are without spots, and the tail part of the body is noticeably narrower than that of the common one. This bluefish belongs to the so-called long-whiskered gudgeon, which many zoologists separate, and quite rightly, into a special species - Gobio uranoscopus. The latter, as can be seen from the Russian name, is distinguished by longer antennae that almost reach the gill slit, a more elongated body, a narrow head, shorter stature and a more cylindrical, less laterally compressed tail part of the body. Near Yaroslavl, fishermen call the long-whiskered gudgeon golzak or kholzak. In addition, long-whiskered minnows were found in the Volga and Kama, in the Kazan province, in Mogilev on the Dniester and in the rivers of the Danube basin. It is probably found, like the black-necked one, in almost all of Russia. According to the information I have collected, bluegill are very numerous along the sandy shallows of the Oka and Volga, and in some places even common bluegill. The Oka and Volga sinets, in addition, differ in their size. Recently, the bluegill was also found in the river. Serdobe Saratovsk. lips., as well as in Kura and Kum in the Caucasus.

The black minnow has a fairly wide distribution. It is quite common throughout Europe and most of Russia. It is, however, not found in Finland, with the exception of the southern parts of Vyborg province; in Lakes Ladoga and Onega, the gudgeon is rare and is found only in the southern parts of these basins, but further to the east it was found by Danilevsky near Arkhangelsk, also in Mezen and Peza, and in later times (by Petrov) - in Vytegra and Onega. Judging by the abundance of minnows in the rivers of the Bogoslovsky district, these locations have a high probability of occurrence. In any case, the gudgeon does not belong to the indigenous inhabitants of the rivers of the White and Arctic Seas and probably spread here in later times. In Pallas's Zoography, only European Russia is named as the habitat of the gudgeon, but it is found in most of Western Siberia, as it is found in the Irtysh and in the Ob (lower reaches), as well as in the Yenisei. In addition, the gudgeon (a special variety of it) is found in the Turkestan region (in the Syr Darya and its tributaries).

The real gudgeon was found only in the upper reaches of the Amu Darya (in the Dayravata River) at an altitude of 2000 feet. Note that, according to some information, this fish is very rare in the tributaries of the Don. In the lower reaches of the Volga and Urals it is quite numerous, and is also very common in the rivers of the Crimean Peninsula. In Kuma and Kura only long-whiskered gudgeon was found, in the river. Tuapse is ordinary. Let's move on to the gudgeon's lifestyle. It lives both in large rivers and in the smallest rivers, is less common in flowing lakes and ponds, and even more so in winter, but, being transplanted into stagnant but clean water or having got there by accident, it multiplies there very quickly, although it never reaches the same size as in rivers. In some exceptional cases, the gudgeon, according to Haeckel, is seen not only in swamps and underground waters (for example, in the Adelsberg grotto), but even in warm springs, like Teplitz, Carlsbad, Baden, etc. In general, he loves clean water and fresh, although avoids very cold and too fast. Usually, throughout the spring and summer, minnows stay on or near rifts, in shallow places with a gristly or sandy bottom, which is where its main name with its many variants comes from. At the end of summer and autumn, minnows are seen in deeper places, also with a sandy or silty-sandy bottom, and are most often found near the very rifts, in small bays, where a small whirlpool is formed.

They are never found in grassy areas during the day, and in general minnows are found in the community of minnows and loaches. In October or November, depending on the area, gudgeons almost disappear and go to spend the winter in ponds or lakes, or hide in the deepest river holes, and since in winter they very rarely fall into seines, it is very possible that they sometimes burrow into the silt.

The gudgeon leads a completely diurnal lifestyle and never swims at night, but then lies motionless on the bottom, resting its pectoral, ventral and anal fins, as if on supports. In the midday heat, it sometimes, also for hours at a time, stands in one place, leaning against a stone or snag, and this immobility of the gudgeon, together with its slab-like body, gave rise to its apt name by the Little Russians - column, column. In general, this small fish is not very lively, although it swims very quickly and can hold on for a very long time and even swim against a fast current. However, on the rifts the gudgeon hides behind rocks, and here it rises upward in pushes from one protection to another.

Due to the preference given to riffles, the river gudgeon, before all other fish, dies from water spoilage by any harmful substances: gas production residues, poisonous paints and other industrial waste. In Moscow itself, minnows also sleep in the summer when it’s hot, after rain, because they can’t stand the warm and smelly water from the hot pavement. Apparently, the long-whiskered gudgeon prefers quieter, deeper and sandy places, while the common gudgeon (in the warm season) stays exclusively on gristly or rocky bottoms. This explains why its belly often has bloody abrasions, especially during spawning. In general, the blue minnow is much weaker and less numerous than the black minnow and has never yet been found in lakes and ponds, and it seems to be very rare in streams and small rivers.

Lake minnows, according to my observations in the lake. White and Tolstoy ponds, which have fairly cold water, stay (in summer) near the shores, on the sands; according to Terletsky, they, however, go into the depths for the summer, to the muddy bottom, and do not go to the shallows, which can be explained by the heating of the water near the shores. The lake gudgeon, at least at night, stands in the depths and is unlikely to hide in the grass, like the river gudgeon.

The latter, even before sunset, becomes clogged with algae and other aquatic plants growing on or near the rifts. Here the gudgeon is completely safe from predatory fish, especially burbot, which does not give it rest at night. In convenient places, experienced fishermen catch a lot of minnows at this time along with loaches and especially spindly spined loaches with a basket, or simply feel them with their hands and pull them out along with filamentous algae, from which all this little stuff gets tangled. As was said, the gudgeon always stays at the very bottom, like a ruff, and extremely rarely rises to the surface of the water, even in fairly shallow places. However, on riffles, the gudgeon sometimes even jumps out of the water completely - upright, in a rather characteristic way, so that such a “playing” blackling is not difficult to distinguish from other small fish. This jumping out is noticed from time to time throughout the summer. According to some fishermen, minnows “jump” before spawning and “break” the eggs; others think that jumping out heralds a change in weather. Minnows, pursued in the shallows by predatory fish, also jump out of the water.

In large and medium-sized rivers they are most persecuted by shereshpers, who prefer gudgeon to any other fish. Probably everyone has seen how a shereshper strikes on shallows and rifts. You can be sure that he swam unnoticed to a school of minnows, crashed into it and hit it with the aim of stunning some fish and picking it up. It should be noted that minnows live very amicably among themselves and are often found in flocks of mixed ages - last year's ones with old ones. Like a bottom fish, the gudgeon always looks for food at the bottom. It usually feeds on small worms, insects, crustaceans, such as cyclops and daphnia, as well as particles of rotten organic matter, which it obtains from sand or silt. In this case, the antennae probably do the gudgeon a great service. In the mud, he gets himself bloodworms, which at the end of summer seem to be almost the main food of this fish, of course, where there are a lot of bloodworms. I even believe that the gudgeon’s retreat into the depths is determined not so much by the freshness of the water as by the abundance of red larvae of the pusher mosquito. The main food of the gudgeon in the spring seems to be the eggs of other fish, which cause significant harm.

In addition to the fact that they intercept those swimming past on the rifts, b. including unfertilized eggs, gudgeons in April and partly in May feed on eggs swept by other fish on the rifts and stones, tearing off the stuck eggs with their thick lips. According to many authors, minnows also eat animal waste, even carrion: Marsigli enthusiastically tells how during the siege of Vienna by the Turks, minnows gave particular preference to the meat of infidels. Nevertheless, the gudgeon is less omnivorous than the barbel myron and consumes mainly animal food, which is proven by the practice of angler fishermen. The spawning of minnows is in many respects still unexplored and presents many dark sides, requiring more detailed and accurate observations. We don’t even know anything about the spawning of blue bream, and we can only assume that it is unlikely to present any significant differences. The river blackfish apparently begins to rub about a month after it emerges from the deep places where it spent the winter. The hollow water finds him already near the shallow banks, where the current is quieter; then, soon, as soon as the river enters the banks, it takes its summer places, i.e., riffles, and begins to spawn. It seems that in large rivers, e.g. Volga, Oka and others, most of the gudgeon, due to their late flooding, enter small tributaries - rivers and streams - to spawn; in the lower Volga, however, according to fishermen, minnows, due to the lack of convenient places, release eggs in crayfish burrows. In flowing lakes and ponds, minnows also go to rivers and streams to spawn.

Here, in central Russia, minnows begin to spawn almost simultaneously with roaches - at the end of April or early May, but there is no doubt that spawning lasts a very long time, almost the entire May and even June, and that the eggs . therefore, it is released in parts, in several stages, and not all at once. It seems to me that this frequency of spawning can be explained by the relatively small number of males compared to females. While in most fish the number of milkfishes significantly exceeds the number of eggs, in gudgeons it is the opposite - there are very few males. They differ from females by their smaller stature, and during spawning by a granular rash on the head, back and upper side of the pectoral fins. According to Blanchard, there seem to be 5-6 times fewer of them than females. Therefore, we can give some credence to the observation that during spawning the female and male actually rub belly to belly, simultaneously releasing eggs and milt. Aquarium enthusiasts - indoor fish keepers - on the other hand, know very well that in order to fertilize the eggs there is no need for them to be directly doused with milk. In stagnant and quietly flowing water, eggs, according to theory, should be fertilized entirely, almost without residue, and the faster the flow, the more milk, obviously, is required for fertilization. Be that as it may, the gudgeon spawns in rivers and streams in a very noisy manner and in numerous schools - in very small places, on cartilage and small stones. At the same time, the minnows stick out their tail and most of the body, except for the head and part of the belly, and hit the water with their tail. In medium-sized rivers, gudgeon spawning is less noticeable: dammed rivers, for example. in the Moscow River, due to the lack of riffles, it rubs mainly under the locks, under which it has been holding in masses since the end of April, attracting many pikes and shereshper. Here it spawns between the slabs and large stones that line the river bottom under the sluice. In large rivers, as has been said, gudgeons release eggs to extremes (in pairs?) even into crustacean burrows. In stagnant cold lakes, for example in the above-mentioned Beloye, which is near the village. Kosina, near Moscow, minnows, according to the information I collected from the tenant of the lake, rub on the sand, in small places near the very shore and gather here in such numbers that the water seems to be boiling. In the middle of summer, a curious phenomenon is noticed here, also probably related to spawning: the gudgeon suddenly begins to gather in fairly deep places in a continuous mass, forming a regular cone, the top of which is on the surface. The quantity of fish can be judged by the fact that if they catch this pile with a seine in a timely manner, they immediately pull out up to 10 pounds or more. It is very likely that minnows finish spawning in this way, since the highly heated water off the coast forces them to move to depths.

Minnow caviar, very small and bluish in color, is released onto stones, cartilage, less often driftwood and, in exceptional cases, onto grass. Here it sticks tightly, sometimes covering the bottom with a continuous layer. Most of the eggs, however, are the prey of the same minnows, which also destroy a great many of the newly hatched juveniles. The flood after spawning has a huge impact on the gudgeon harvest, since almost all the eggs and almost all the fry are carried away by the current. But under ordinary conditions, the fry manage to leave the rifts for quieter, albeit shallow places, namely, shallow sandy or, more often, sandy-muddy shores, where they remain throughout the summer, until mid-August and later, feeding exclusively on daphnia. cyclops and other small animal organisms that they find in the mud. It is very possible that juvenile gudgeons also feed on rotting substances in the early period of their lives. Small minnows crowd around the shore in clouds, choosing the smallest places, constantly poking their noses into the shore. They grow with amazing speed, comparatively faster than all other fish. According to my observations in the Moscow River (in 1889), the juvenile gudgeon at the end of July was already almost an inch tall (from the head to the end of the tail), and by the end of August it reached more than 1 1/2 in. Last year, 1890, which was distinguished by an unusually early spring, early spawning and, as a result of a warm summer, an abundance of food, gudgeons grew even faster.

In ponds and lakes, minnows never grow as large as in rivers. Large gudgeons are found both in small rivers (for example, in the Setun River near Moscow) and in large rivers. I met the largest minnows in the Volga, near Yaroslavl: they were more than 5 inches long and up to 2 inches thick. In the Moscow River in August and September, mainly three-inch, fifteen-month-old gudgeon are caught; gudgeon per quarter - this is for the 3rd year. It seems that minnows do not spawn until they are almost 2 years old. A five-year-old gudgeon is, presumably, very rare: in the Moscow River, where it is exposed to great accidents, it is unlikely to reach such a respectable age. As for the blue minnow, it grows comparatively very slowly, and a year and a half year old is never longer than 1 1/2 inches. It should be noted that by autumn, juvenile minnows of both species of different sizes are found, which is explained by the duration of their spawning.

Due to its size and location, the gudgeon obviously cannot have the slightest commercial significance. It is caught with gear only in small rivers in the absence of larger fish and only for oneself, and not for sale, since the market value of the gudgeon is insignificant, with the exception, however, of the capital and large cities, where the gudgeon is sold quite expensively, but in very small quantities, so as it has incomparably fewer consumers than the ruffe, and is delivered to live fish cages in small numbers. Where there is a lot of gudgeon, it is caught in the summer or in the fall with nonsense and duds from the rarest canvas. In spring, in hollow water, in some places it comes across marks; later, during spawning, it crowds into frequent peaks in masses, if the place for them has been successfully chosen.

For hunter-fishermen, the opportunity to get gudgeon, which is the best river bait for all predatory fish, is of no small importance, and therefore, in addition to the mentioned methods of fishing, it is necessary to point out others, although more convenient, but almost unknown to us.

In Western Europe, especially in France, where the gudgeon enjoys great respect, much more than in our country the ruffe and even the burbot, these methods, very simple and handy, are very common. Firstly, a lot of gudgeons are caught here with special small and frequent small capes, which are thrown from a boat or near the deep shore, after first stirring up the water with a pole or oar. But our game is not worth the candle. This fishing is difficult, and it is unlikely that anyone in Russia will catch such a small thing this way.

It is much easier to fish with a lifting net, which is rather little known among us. This, one might say, is a special projectile for catching minnows. The latter is often caught in this net by the hundreds at a time; but these so-called carrelets are also very suitable for catching all kinds of smallmouths in general, and especially the whitefish (Leucaspius), although with modified techniques (see “Verkhovka”). On the Vistula, as far as we know, all kinds of large fish are caught in such lifting nets, but of large sizes and in muddy water. To catch minnows, a fine net of strong threads 2 arshins square is sufficient; This net is strung on a strong twine, so that it also has the shape of a square, then two strong and smooth sticks (walnut, birch) 2 1/2 arsh are tied crosswise to the corners. length; at the point of intersection of the sticks, these are tightly tied. This results in a shallow mesh bag, stretched with cross-linked sticks. If you now tie a more or less heavy lead sinker to the center of the net so that the net sinks to the bottom, then, obviously, if you quickly lift it by the rope, the sticks should bend and the net will form a more or less deep bag, from which very few people manage to jump out minnows and ruffs, like fish, crawling along the bottom and reluctantly rising to the top. The entire success of catching gudgeon with a lifting net is based on this. Only usually a net, or, more precisely, sticks, in the place where they intersect, is tied to the thin end of a more or less thick and long stake, up to 3-5 arshins, the kind used for basting. The heavier the free thick end of the pole, the easier and faster the wet net will rise from the water. They are caught on the rise - from locks, bridges, especially floating ones, gangways and rafts, less often by wading and from boats. Before lowering the net to the bottom, the water is strongly agitated - this is necessary, since the turbidity, as we will see later, is the main bait for the gudgeon. However, if the gristly or rocky soil does not allow this, then you can lure minnows by throwing small pieces of clay with bran into the net; sometimes it is also good to tie a bag of radish with clay mixed with bloodworms and small worms to the middle of a wooden cross. The minnows standing below, seeing the streams of turbidity, rise along it to the net and in a short time crowd into it in dozens, almost hundreds. When fishing with a lifting net, of course, some skill and agility are required; It is also very important to be able to balance the thickness and flexibility of the sticks and tie them to the pole so that the net rises completely correctly, in horizontal planes, and not sideways. I advise all amateur fishermen to acquire a lifting net, as it is absolutely irreplaceable. Moreover, it can easily be made collapsible: the poles can be removed and untied, and the long “armature” can easily be made foldable, in two parts, so that the entire projectile can be easily transported even in railway cars along with other fishing accessories.

As has already been noted, in our country minnows are caught in the tops, like all other fish, almost exclusively during spawning. The reason is that top fishing with any kind of bait is almost unknown in our country. Meanwhile, in Western Europe they use the latter with great success and catch all sorts of fish at all times of the year, except spring, since fishing during spawning, that is, in the spring, is certainly prohibited there almost everywhere. Our bait is b. including the top itself or another similar tool made of twigs and shingles as a convenient artificial spawning ground. In Germany, according to Ehrenkreutz, carrion, cakes and cheese are placed in the tops of minnows to bait them. There, instead of tops, they use very original equipment, namely horse and bull skulls, which are immersed in water at certain places. Minnows enter the skull through the occipital foramen and, when quickly rising, do not have time to get out.

French bottle fishing for minnows is much simpler, more interesting and cleaner. In essence, this is the same fishing in the top. They take a simple bottle, or even better, a white glass bottle, with a strongly concave bottom, and drill a finger-thick hole in the middle of the latter. In Paris, special glassware is sold for this purpose. The neck of the bottle is plugged with a drilled stopper (or a glass tube is inserted into it), then small worms, bloodworms or even bran are placed into the shell through an artificial hole, then carefully lowered into the water along the river with the neck against the current. Water passing through the throat carries with it part of the bait, which attracts minnows to the hole at the bottom; fish enter this hole, but are almost unable to leave the trap. Sometimes in a few minutes more than a dozen are filled into such a bottle.

In our country, most of the minnows, both for food and for bait, are caught, it seems, with a fishing rod. Beginner fishermen especially love to fish for minnows, as this is the easiest and most fun fishing, perhaps even more rewarding than fishing for ruffs and perches. Fishing with a fishing rod begins in the second half of April, more often in May, i.e. after spawning and during low-water periods, and continues until October and later, first in rifts and shallow places, and with the onset of frost - at a decent depth. Moskvoretsky fishermen manage to catch gudgeon almost all year round, since they not only fish for it in October, but even in November and early December, when the river has already become dry. On the first ice, however, they catch minnows not at depth, but in relatively shallow places with a gristly bottom. In the middle of winter, the gudgeon rarely becomes prey for the capital's winter anglers and, obviously, hides in the depths, does not take food, and perhaps hibernates or even buries itself in the silt. With strong thaws, it emerges from its winter camps and in February for years it is caught in large numbers, as in March, until the opening, ceasing to be caught in bad and cold weather. As for the time of day, the gudgeon, like a daytime fish, takes the bait only from sunrise to sunset, and with the onset of darkness the biting stops. It takes best in the early morning shortly after sunrise. It bites the worst during the day, especially in hot weather. The state of the weather seems to have a small influence on the intensity of the bite of this fish, but before bad weather you will never catch many of them. On the contrary, after rain, when the water becomes somewhat cloudy, the gudgeon takes more greedily. In most cases, gudgeons are fished using the lightest 4-5 arshin float rods with thin fishing line, b. including three-haired, and from the shore. The float is the lightest - feather, cork or sedge (even better from kuga), and the hook is either 6-8 No., ordinary, if you fish with a worm, or No. 10, with a long shaft, i.e. bloodworm, if the bait is a bloodworm . Since the gudgeon is a completely bottom-dwelling fish, the hook must certainly go along the bottom, touching it. However, in very deep muddy places, the gudgeon takes higher. Where there are a lot of minnows, they are fished for. h. on two hooks, with the upper one tied on a short leash above the lower one by an inch. The bait is mainly either a dung worm or a bloodworm; the first - in spring and summer, the second - in autumn, from August. In quieter places it is better to fish with a whole worm or half; on riffles, it is more profitable to plant a piece of a red worm or, even better, a piece of an ordinary iron ore worm, like a ruff. Bloodworms are attached, as always, by threading the hook tip below the head, in the amount of 1-3 pieces. As for other baits, they are of little use for catching this fish. Not only do minnows not take any “bread” bait (however, I once caught 2 minnows on bread in Lake Beloe), but they are not particularly willing to grab, for example, maggots and ant eggs; The latter is more likely to be caught by bluets than blacks. Where there are a lot of gudgeons, you can catch several hundred of them a day, but not otherwise, however, than by using bait, which is not known to every fisherman. This bait consists mainly in stirring up the water: the gudgeon catches the mud and, forgetting all caution, approaches the moons, which has probably been observed by every bather. With each break in the bite, it is necessary to produce artificial haze - with an oar or a pole, on the pointed end of which it is very useful to put an iron tip: the French nail iron circles to the end of the pole even without this, the so-called. pilon, they don’t go out to catch minnows.

Not long ago, Moskvoretsky industrial fishermen developed a special, very prey fishing method, which they use most often in late summer and early autumn. Having found a gudgeon in a riffle, the fisherman stands on the boat across the current and casts two short bottom fishing rods (or fillies) with doubles so that the bait lies on the bottom -4 arshins from the boat. Then he stirs up the water vigorously, repeating this as often as possible. The bait is usually bloodworms, and in the summer - pieces of worm. With a good choice of place and a good bite, a nimble angler can easily catch 500-600 pieces even with one fishing rod, and minnows are very often caught in pairs, like ruffs (see <Ruff>), rarely breaking off, since they are hooked by a bullet. In general, the gudgeon takes extremely accurately and rarely breaks, especially since its lips are very strong. However, the small bluegill, which has a relatively small mouth, bites relatively very sluggishly, hesitantly and often sucks bloodworms, which is why fishermen, if they catch a bluegill, immediately change their place. The gudgeon is a very tenacious fish and is almost irreplaceable as bait for predatory fish. In Western Europe it is considered an excellent food fish for salmon, and in England it is often kept for long periods in troughs and baths.

When using the described blowing devices (see “Pike”), minnows can be transported over considerable distances. In our country, gudgeons are mostly used for fish soup, and often together with ruffs, since fish soup made from minnows alone, almost devoid of mucus, is not very rich. Less often, gudgeons are eaten in a frying pan with sour cream; the French are big fans of gudgeons fried in onions or crushed breadcrumbs, in Provençal butter. Gudgeon soup is a very light and digestible food and is given even to feverish people. Minnow meat is white and somewhat sweet. Lake gudgeon, especially pond gudgeon, always smells somewhat like mud.

Author: L.P.Sabaneev

FISH CATALOG